Farming at Parsonage Farm

(Board 3)

A farm was, and is, a business. It has to be sustainable - it has to endure, which needed the workers, crops, livestock, land, suppliers and

and customers all to play their part together. And the farmer had to

manage all these parts of his business, looking after each element.

Arable farmers were vulnerable to bad weather, even more if it happened over a period of years – as it did between 1873 and 1895.

Livestock farmers were vulnerable also to diseases for both sheep and cattle, which were very common in the middle of the century.

John White was farming both arable and livestock. He had to make decisions every day: about what work could be done in the weather at the time, about what varieties of wheat, oats and barley to grow, what fodder crops to cultivate, what animals to keep – and how to keep them safe.

He had to know his customers, and respond to their changing requirements and what they would pay. And he had to know what his suppliers could provide – and at what price.

An original painting of Parsonage Farm, believed to be by Herbert E Bultler and painted in 1882 when he was a Royal Academy student.

John White was both an arable and livestock farmer. He had to make decisions every day: about what work could be done in the weather at the time, about what varieties of wheat, oats and barley to grow, what fodder crops to cultivate, what animals to keep – and how to keep them safe. John gave the orders for the day to his farm workers through his foremen – he had one at each of his farms.

He had to know his customers, and respond to their changing requirements. And he had to know what his suppliers could provide. John started farming with his father and brother at Appletree farm in Chorleywood. Shortly around the 1841 census he takes on the farm at Parsonage Farm, Rickmansworth, with fields immediately adjacent.

John White regularly participated in the local “Fat stock and Poultry Exhibitions” which took place in the Agricultural Hall, Watford. On occasion he won prizes, of both monetary value and prestige.

Morning Post, 15 December 1875

The crops at Parsonage Farm

John White was mainly an arable farmer, but he kept a number of animals. They needed feeding in winter, and crops for fodder for them were an important consideration. John White used crop rotation methods along with his knowledge of the land and the quality of its tilth.

The arable crops are described below

In the 1840s he grew: turnips (the sheep ate the foliage, and then the turnips were dug, cut up and fed to them in pieces), rye grass as hay for the cattle and clover as well as oats for the horses.

In the 1850s he had clover, trefoil and bents, as well as turnips and clover, ten years later hay grasses, sanfoin, mustard, rape, mangel wurzels, cabbages and swedes.

In the 1870s, with the depression set in, the diversity of his crops was reduced, and clover, hay grass, swedes, turnips and mangel wurzel were joined by kohl rabi, a member of the cabbage family.

By the late 1880s sanfoin was back, along with hay grass, swedes and turnips, but now he was also growing potatoes.

JW Diary Volume 6 , June 9th 1860

“I live in hope for I have, many times, been on the verge of despair & yet all has come right in the end.” John White, farmer, 1 July 1879 |

John White’s arable crops

Mr John White grew wheat, oats and barley.

The wheat, harvested in July, was sold to millers and corn factors, mainly for flour for making bread (some was sold as cattle feed as well). He experimented with several varieties, among them hardy Chidham, Ducie, Golden Drop, Red and Talavera, which originated in Spain and was favoured by millers for a good quality flour. He also tried an Australian wheat, but wasn’t happy with it.

[Bing photo of wheat]

Oats were important for feeding horses, which were the main motive power at this time. Much of his crop (he grew Black Prince, White Tartary, White Poland and Black Tartary, sowing in either September or March) no doubt went to London, where many thousands of horses were used. But he had about twenty horses of his own, and many neighbours using them, so he had plenty of places to sell oats.

Insert photo of oats and horses?

Barley was mainly used for making beer. It was sold to brewers and to maltsters, who ‘malted’ it before it was missed with boiling water in the brewery. John White grew Persian barley among others, sown in the autumn and harvested in July, and sold it to Salters Brewery in Rickmansworth, and also to the Watford brewers – and he even sent samples to the centre of British brewing in Burton on Trent, in Staffordshire.

Photo of Salters brewery/Malthouse?

These were the main products of the farm, so the failure of the arable crops due to bad weather was a very serious matter indeed.

Fertilisers at Parsonage Farm

Keeping the field in good health had always been done by rotation of the crops they grew, and John White did that with care.

But the need to fertilise the fields has been well known since ancient times. In Hertfordshire it was often done using cattle or horse dung, composted and spread by the labourers.

Insert picture of the dung cart or London dung on barge?

In winter sheep might be put to graze on turnips grown in last year’s grain fields – they were confined to a small area using wooden hurdles (‘folds’), which were moved as the fodder was eaten up. This was a job for the shepherd.

London produced huge amounts of ‘manures’ – horse dung mixed with straw, or ashes, or animal bones…. Mr White, being close to the canal, was able to take delivery of manure from London by barge (about 25 tons per load), which usually came to Batchworth Bridge wharf and was unloaded and taken by his labourers and spread on the fields. It was valuable enough for him to go often and supervise the unloading himself.

He used Two Stones farm as one of his main dung stores.

But these traditional fertilisers only went so far. During John White’s time a range of new fertilisers became available, and you can read about them in the below.

Modern Fertilisers at Parsonage Farm

John White kept up to date with modern developments in farming, and used them as soon as he was happy with them.

One was the availability of ‘guano’, the composted droppings of sea bird colonies found mainly in islands off the coasts of Peru and California. Rich in nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium (N,P,K), it was known about for many centuries, but only became popular in Europe between about 1840 and 1910.

http://bbprivateer.ca/?q=panther via; https://thegardenstrust.blog/2...

John White first used guano from 1847, spreading about 2 hundredweight to the acre (much less than dung) on his newly sown swedes and turnips. He was still using it in 1892.

Another important fertiliser was superphosphate, developed at Rothamstead by John Lawes from 1842. Very rich in phosphorus, it gave high yields. Being very soluble, it was taken up quickly by the crop plants – we now know that it is a source of water course pollution.

John White first refers to superphosphate in the summer of 1860, when he was mixing it with guano on his fodder crops, and he used it regularly after that, spreading it at the rate of about 3 tons to the acre.

Preparing the land for sowing

In early May 1860 Mr White recorded his Mangold ground of 6½ acres had been prepared as follows:

Fallow’d up immediately after Harvest & harrow’d down to allow the annual weeds to vegetate in November.

It was Dunged with London Dung, plough’d in thin and the ground subsoiled under, in which state it lay till the end of April, when it was well harrow’d down & scarified and the low Stuff picked off

– then Crop Plough’d and well harrowed in again, then drawn into Bouts* and then Coat of London Dung put in between and on about half of the field, about 2½ [cart loads – about 2 tons] of Superphosphate & Guano to the acre besides bouted up & the seed Drilled with a Small one-row Essex Drill –

I now leave the rest to Providence trusting him for a good Crop[P2] .

The total cost of this:

3 Ploughings £1.10.0 6½ acres £9.15.0

1 Subsoiling – 1 Scarify £0 15.0 -“- £4.17.6

4 Harrowing, Picking £0 5.0 -“- £1.12.6

Bouting & Bouting up £1. 0.0 £6.10.0

3 Boats Manure £24. 0.0 £24

2 Do. & 16 Load Bought £21. 0.0 £21

Guano & Superphosphate £3. 0.0 £3

Seed & Drilling & Dung Spreads £3.15.0 £3.15.0

______________

£74.10.0

- A ‘bout’ was a ridge left between ploughed furrows[P3] .

Extract from John White’s Diary image 74, Volume 6, May 3rd 1860. Rickmansworth museum

The Harvest – gathering the crops

The harvest was a major event on a farm like the Parsonage. In a good year it was finished before the end of August. In some years it was complicated by bad weather – it might have been delayed (more than once, it wasn’t in until mid-October, and even then very poor), or it might have been flattened by wind or rain, which greatly complicated cutting it.

Harvest was hard work. The normal workforce wasn’t big enough to gather all the crops, and special contractor help was needed. These people don’t often have names in these diaries, but in 1847 (a bumper year) a man called Turner had his gang on the farm for exactly a month before being paid off on 26 August.

[Bing; Victorian reaper machine]

Reaping machinery was being introduced and is referred to by John White in his 1847 notes. But generally, it continued to be cut mainly by scythe for a number of years. Thrashing was done by machine, however (driven initially by horse, later by steam) over the following winter months

The end of Harvest was called Harvest Home, and was celebrated with a big dinner with cider and beer, paid for by the farmer, before the harvesters went off – and the farm’s workers returned to normal activities. John White held strong views about this:

Uxbridge & W. Drayton Gazette, 14 Feb 1885

The animals at Parsonage Farm

Parsonage was a mixed farm. Aside from the working horses, Mr White had cattle and sheep and some pigs. They were kept for meat (we see no evidence of dairying), and he also sold the wool of his sheep[P4]. He also kept some chickens for domestic use and a few ducks for the pond for “dear Sophie”

Most of his sheep were Oxford Downs, a large animal producing short white wool and good meat. He seems also to have kept the smaller Dorset Downs and hardy Cheviots.

He doesn’t, however, note the breeds of his cattle but it is noted that John White kept the Jersey pedigree book for Lord Chesham. John also takes his cows to mate with “Corporal Trim” a known pedigree bull.

21st December, 1860 Volume 6

His were well-loved animals – many of the cows had names, and when they calved they were recorded with care and pride[P5] .

May 10th 1860 Volume 6

The animals were vulnerable to disease. Sheep and lambs got scour (from what they ate - Mr White was very concerned in 1869 that his efforts to provide especially good feed hadn’t worked), and other problems; and there were serious outbreaks of cattle plague and foot-and-mouth, which were controlled then as now largely by quarantine and culling.

John White entered his stock into the fairs at Watford and further afield at Smithfield and the London Metropolitan.

His horses seem to have done better, but in 1847 he lost a horse (‘Punch’) to illness, and noted that it was the seventh in six years. He would select his horses for their ability to work the land but some were needed to draw a carriage, or to ride for pleasure with the fox hounds, or on his rounds of inspection to check up on the work being carried out by the many farm hands.

[Vanity Fair, caricature, a Masters’ meet, 1895 Lord Lonsdale on the left . Wikipaedia]

The horses he rode to hounds sometimes fell and were injured, which upset him, and in the spring of 1892 the stable had an outbreak of equine influenza, which concerned him greatly. John White was very conscious of the effects on both animals and farmers, and was on several committees formed to deal with these outbreaks. Veterinary science was not as advanced as now, although there were ‘vets’ and he used them.

Cattle Plague and Foot and Mouth Disease

As we were reminded in 2001, animal disease was a real problem for farmers and the public. It was much more so in Mr White’s day, and both it and Cattle Plague broke out. They had to be controlled.

Are there pictures/newspaper clips, handwritten clips of quotes below?

Oct 25 1873, “… at St Albans on the Cattle Disease Committee.”

Feb 1877,“… to St. Albans on the Contageous Diseases Annual Act. Comtee. The Cattle Plague having broken out in London & … other places, the Comtee met to day to make such regulations as they thought desirable to prevent the introduction of the disease in the County & to regulate the removal of Animals & to Close the County against all animals outside it.”

April 2nd 1877, “… to look at some Heifers of Mr. George Wilds as he wish’d to remove them to some land in Moor Lane, which according to the Cattle Plague orders he could not do without an order which after inspecting them & finding them healthy, I gave him…”

April 10 1877,“… Lord Cheshams Sale of fat Stock … by Alfred Sedgwicks wish, as I might be required to sign some licences for the removal of Cattle under the Cattle Plague Orders.”

November 1883, “…at St Albans …the Comttee on the foot & Mouth disease. Dined at The Pea Hen at the Market Table…”

November 1883,“… London … a meeting on … the Movement of Cattle regulations in the Various adjoining Counties & to assimilate the regulations instead of the present diversity. No agreement could be arrived at as different opinions are held in different Counties

You can read more about the government of the day’s early response to this devastating disease; https://api.parliament.uk/hist...

Even John White himself got into trouble.

October 1883,“… I was summoned to appear before the Magistrates for Sending 10 Cows through a foot & mouth infected district altho’ I had a licence sign’d by a Magistrate & tho’ no disease existed in the neighborhood at the time. I was fined 50/- for the offence and 20/- Costs.

This would have been a considerable sum of money in those days. There were 12/- (shillings) in £1 (one pound sterling), so this equates to several hundred pounds at today's values. |

This I think an abominable injustice and a great Stretch of the power Vested in the Magistrates as I had a licence granted me by a Magistrate & I had nothing to show me that it was an offence to move Them through an infected district and in fact the district was free from disease tho’ the same had not been declared by the Inspector which he shd have done.

I have not paid the fine yet & shall not do so until I enquire about it.”

He was very cross about it!

You can read more about Foot & Mouth disease which affects cows, sheep and pigs and is still a problem today: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/fo...

John White was a man of principle and lived an honest, hardworking exemplary life, so we understand how vexed he would have been |

[P1]Explanation to young audience

[P2]Use JW’s handwritten image for this?

[P3]Add explanation of what the mangolds are used for?

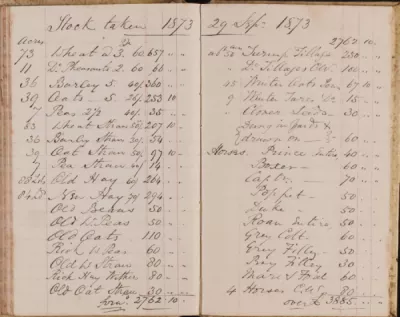

[P4]Image of JW stock coming first?

[P5]He refers to their colours, some references to breeding with Lord Chesham’s jersey’s and keeping the pedigree book, reference to be found?