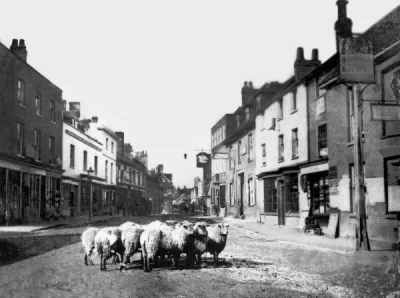

Rickmansworth as John White knew it

1841 to 1896 (Board 2)

By 1841, as the newly married John White was starting his diary, Rickmansworth was a small early Victorian town. Paper making was its main industry, but agriculture was still the occupation of most of the people. The parish included Croxley Green, Mill End, Chorleywood, Maple Cross and West Hyde, while Herringsgate was still just a farm.

Moor Park, the largest of several houses lived in by wealthy people, had been bought by the Marquis of Westminster, with Henry Fotherley Whitfeld’s new manor house Rickmansworth Park in the same style.

The Bury, Scotsbridge House, Langleybury, Moor House and other ‘seats of the gentry’ provided employment ‘in service’ for some.

The Bury, Rickmansworth

The silk mill had just been enlarged, and Salter’s brewery was developing its estate of pubs. There were three wharfs served by the Grand Junction Canal, and the London Road turnpike started at one of them. St Mary’s Church had been completely rebuilt and enlarged in 1824, but was still the only Anglican church: non-conformism was strong, however, with Methodists and Baptists both with their own establishments.

The market was by now defunct, with Watford’s the only agricultural market nearby.

There was still the annual ‘cattle fair’ in November and the ‘hiring fair’ in September were still strong. There was a paper mill, a brewery and a tannery at Mill End, and the other trades and ‘makers of things’ scattered around the area

Life in the town is explored below.

The developing town – the roads

The roads of the parish were largely in the hands of the district Highways Board set up in 1862 to take over this part of the Vestry’s business – and lasting until the new civic authorities were set up in 1894. Rickmansworth was part of St Albans District. John White was a member of it in 1885 and 1886, attending regular meetings, although giving few details.

Most road surfaces (called ‘macadam’ after the road engineer) at this time were of gravel, flint or granite, broken into small pieces and compacted. Some will still have been unsurfaced, however, and very muddy and rutted. Rickmansworth’s roads were never cobbled.

[ credit Geoff Saul collection, Rickmansworth Historical Society]

Most urban roads of this time were relatively narrow, confined between the rows of houses on each side and just wide enough for two carts to pass. High streets were generally wider, especially if (as in Rickmansworth) a market had been held there. It was the advent of the motor car that caused roads like Church Street to be widened, often at the expense of the foot way.

The Reading and Hatfield Turnpike, which formed most of Rickmansworth High Street, was declared a Main Road, although still collecting tolls until 1882. As the Chorleywood road it bordered Mr White’s fields, so he had a vested interest in it. It seems he supplied flints to the trustees:

on 18 April 1879,“Miss Robinson from Wycomb call’d … about my a/c for Flints by order of her Grandfather Thos. Robinson the Surveyor of the Reading & Hatfield Road.”

The developing town – the Railway

The London and Birmingham Railway had come to Watford in 1837, and John White was among those who used it almost from the start, day-tripping into London in the summer of 1846 (the first diary volume we have). He doesn’t, though, suggest any business value at that stage.

Mr White recorded seeing the cutting of the first sod of Lord Ebury’s railway (the branch line to Rickmansworth from Watford) on 22 Nov 1859. It opened in late 1862.

[credit Three Rivers Museum’s own collection]

This was directly helpful to him: he was taking deliveries by the end of 1863, and using it to go into Watford as well as to travel more widely. He was to be a regular rail traveller, and fond of the LNWR, for much of the rest of his life.

The White Bear pub, showing LNWR poster

The arrival of the Metropolitan Railway in 1886 caused him more direct difficulty. As it came to Rickmansworth from London the main concern was about the diversion of footpaths and helping people being affected by it – it didn’t touch his land at all, although it certainly hit others.

But in 1887 the extension to Chorleywood and beyond started, it cut straight across the Parsonage farm, and caused him a great deal of heartache – it was in fact the beginning of the end of Parsonage Farm, certainly as John White had known it.

One of the finest Whit Mondays I can ever remember. A tremendous influx of people down by the Metropolitan linerunning all over the place; over corn fields and grass all alike to them”.

6th June 1892

The developing town – the Chartists

John White took an interest in movements such as Chartism, although as a Tory voter (which he certainly was) he won’t have been a supporter. But on 20th July 1846 he wrote,

“Self at Rickmansworth Fair. Dull trade and sold nothing. Went on the Fortune [probably Fortune Common – at the bottom of Scots Hill] in the evening to hear Mr. O’Connor speak at a Chartist Meeting.”

O’Connor had bought the land in March 1846, and it was to be settled by May 1847. But the industrial workers who came in to the 35 small plots at ‘O’Connorville’ were not farmers: some neighbours gave help, but there is only the slightest hint in the diaries we have that John White was among them.

https://www.historyhome.co.uk/...

The experiment was collapsing by 1851, and was wound up and sold off in May 1857

John White’s letter was clearly used as an example of the economics of farming for small holders, in connection with a Unions and agricultural strikes meeting when

Mr. Charles Lattimore, a farmer from east Herts, in a speech reproted in various newspares, quoted directly using John’s words:

Extract from The Western Times, 15 July 1873 entitled “Agricultural Strikes and Unions”:

"... labourers would not allow their children to be corrected and thought that this want of discipline was a permanent barrier to the improvement of their condition. He was also strongly against the idea of labourers organising themselves into a Union ... capital represented the savings of labour; and if the labourers, misguided by those who taught them that capitalists were their enemies, would not save but insisted on destroying the capital of others, they would lead to the ruin of the country.

The developing town – commerce

Rickmansworth, like most small towns, didn’t have a regular banking service, although some local solicitors had been licenced as banks since about 1806. Then in 1851 the London and County Bank announced that the manager of its Uxbridge branch would attend in the town on a Friday, and it opened a branch properly in 1856. John White was a customer. The bank built a proper branch in the High Street in 1890.

In the 1841 Census there were six attorneys (and one banker), three Excise Officers (probably because of the brewery), three land surveyors, the postmaster, fifteen teachers, two stationers, five doctors, two vets, four wharfingers and five clergymen. A perfumier completed the list of ‘white collar’ professionals.

Other occupations were ‘in trade’ – shoe makers (29), tailors (21) and dressmakers (17), bakers (21), butchers (14), smiths (27) and wheelwrights (7), bricklayers (33) and carpenters (42), gardeners (33), general labourers (29), papermakers (130) and rag sorters (60). 18 people worked in the silk mill, and just 11 said they were shopkeepers, with 19 grocers.

Eighty women were straw plaiting – vital to a family economy – and 170 were ‘in service’ (there were 91 men in service as well).

https://www.hatplait.co.uk/his...

And there were 59 farmers/bailiffs, employing 582 agricultural labourers.

Of 1222 people with no occupation stated, many will have been simply

working on the land or otherwise in the family business, but we don’t

know. Agriculture dominated.

As the century wore on, the balance of occupations changed, although the nature of the town did not. The arrival of the railway in 1862, and further in 1887, allowed more people to be resident here while working in London, or even Watford.

[https://www.hertfordshirearchi...]

And more people came to be working in the ‘new’ occupations – police, the railways themselves, sand and gravel digging, watercress. Long-distance coach travel had given way to the railway, but short-range ‘omnibus’-type services were appearing.

So new white-collar occupations – clerks, printers, booksellers, clergymen – took their place alongside the traditional butchers, bakers, dressmakers and builders listed in 1841. And ‘engineers’ were beginning to appear, and engine drivers, as steam power took hold. More doctors came on the scene, although generally mainly for those who could afford to pay.

Some businesses, for example Beeson the ironmonger, Franklin the maker of soft drinks and Jones the wheelwright, were to become quite large during the period.

John White was himself part of this changing scene. Not only did he evolve his cropping, but he increased his market (and range of suppliers) by adopting some of the new techniques. But the agricultural depression from 1875 will have put a small number of farmers out of business, or at least forced them to reduce their workforce: Mr White seems to have looked to provide work where he could, but times will still have been hard for many.

Watford Observer, 21 January 1871