The Metropolitan Railway - and Metroland

Extending London to include us in its suburbs

This article draws on Denis Edwards and Ron Pigram’s The Golden Years of the Metropolitan Railway (London, 1983) and Metro Memories (1985)

We live in Metroland. It’s easy to forget the extent to which our area is a product of the desire of the Metropolitan Railway to provide itself with passengers as it moved its services out of London towards the Midlands – a major change to the very nature of the countryside of Middlesex, southwest Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire, with very little Government influence or control and no public opposition.

The very name was coined to describe the part of the Chilterns, and the approaches to it, which was to be reached by the railway. The idea was to draw Londoners out into the open air, first to visit and then be taken home again, and later to live in homes made available by the railway company, and ‘commute’ to ‘town’ and home again.

The Metropolitan Railway, the first Underground, was intended to solve the increasing London traffic and transport problem in the 1860s. Initially steam powered, it expanded quickly into Middlesex, reaching Rickmansworth in 1887: electrification began in the early 1900s, with steam taking trains onwards from Rickmansworth even after the town was reached by electric power in 1927.

But the most remarkable feature of the life of the Metropolitan Railway was its realisation that leisure and happiness were marketable commodities that Londoners were willing to pay for: and it pursued that market with extraordinary determination and skill. Much of this development was going on in the late 1920s and 1930s, at a time of widespread economic hardship: but even that did not stop the spread of Metroland.

The full story of the Metropolitan Railway is summarised in its Wikipedia entry https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metropolitan_Railway. Work had started in London in 1860, and the railway first opened in 1863. Extensions (and rivals) appeared rapidly, and the first moves towards the Chilterns started in 1868 to Swiss Cottage. Harrow was reached in 1880, Pinner in 1885, Rickmansworth in 1887 and Chesham, deep in the Chilterns, in 1889.

A local ‘item’ is that in 1887 the Metropolitan Railway Extension heading from Moor Park to Rickmansworth was planned and authorised by the Extension Act to cross Croxley Common Moor, which was owned by Lord Ebury of Moor Park. The Metropolitan Railway Company could not reach an agreement with Lord Ebury, who had asked for £12,500 and had declined the offered £5,000, and asked that a jury be convened to make a decision. They met in March 1887 at the Masonic Hall in Watford, and decided that Lord Ebury should be paid £3,000 for his land and £3845 in respect of damage to his other interests – a total £6845. No doubt honour was felt to have been satisfied.

We should remember, too, that the Metropolitan Railway carried a great deal of freight traffic, coal and gravel as well as ‘goods’, beside the passengers who were the main target of the initial development. But this article will concentrate mainly on what it was like to live round here – ‘here’ being in Metroland.

The 1904 Guide to the Extension Line can be seen as starting a new leisure industry. It listed meetings of the local staghounds (Londoners could take their own horses on the railway for a day’s hunting), suggested bed and breakfast accommodation in Wendover – and provided a list of country walks. Walking and cycling soon became hugely popular leisure activities for Londoners on their days off, and were strongly promoted by the Company. And it is arguable that this glimpse of the open countryside then led Londoners over the next twenty of thirty years to buy (or rent) houses in Metroland and travel into London daily.

We should bear in mind that a severe depression in agriculture had affected the country, and this area in particular, since 1870, with increasing imports of grain and meat products in steam-powered and refrigerated ships from Australia and North America. Agricultural land was widely available, and the population pressure of central London was in need of an outlet. The Metropolitan Railway was very well placed to provide that.

The Metropolitan began developing residential estates by forming the Metropolitan Surplus Lands Committee in 1885. Its first development was at Pinner, but already by 1884 a local land developer had been selling plots in Northwood on a huge estate of over 750 acres. The 1904 opening of the Harrow and Uxbridge Railway gave a real boost to the development of what would become Metroland, and the Uxbridge newspaper welcomed the growth of Uxbridge into a ‘first class residential development and health resort’ when the line opened in June 1904.

An article in the Watford Observer on Sept 24th 1887 had already repeated an article in the Pall Mall Gazette, headed ‘The Annexation of Rickmansworth’. Reporting a walk along the new line from Pinner, it observed that the railway journey to Rickmansworth from London via Watford (Lord Ebury’s Railway) was circuitous and off-putting: but the new railway ‘will bring to sleepy Rickmansworth activity, prosperity and villa residences’.[1] That didn’t happen at once: the same Watford Observer issue, reporting on the first train, was rather disparaging about the Chairman of the railway, Sir Edward Watkin, and his flair for publicity and promotion – it felt that the publicity for the event was much less than that for the opening to Pinner, and the reporter had tried to buy a ticket to Rickmansworth on that first train but found the staff unaware of it. Very few people travelled past Pinner, and he was very rude about Northwood – ‘why people should want to alight at Northwood or get in at Northwood it is impossible to say. I did not even see the cowshed which I am told is the only building within sight of the station.’

He was only slightly less rude about Rickmansworth, where ‘Sir Edward clearly expects some business will be done’. He was the only paying passenger to alight, and he travelled back alone, ‘undisturbed in my conjectures as to what is the ultimate object of Sir Edward Watkin in extending the Metropolitan Railway through miles of countryside which practically has no inhabitants’.

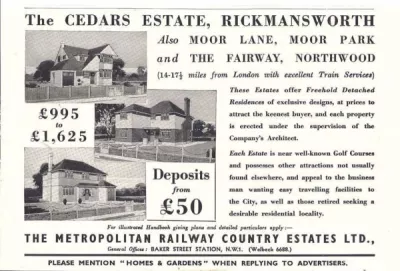

It seems fair to say that Watkin had much clearer idea of the object than did the Watford Observer’s reporter. Northwood was to become the centre of the Ruislip-Northwood Garden City Project promoted by the local council (the first to do so) under the Housing and Planning Act of 1909, and basing the concept on Letchworth Garden City then being built, although the development was halted, as so much else, by the First World War. In those pre-war years the Metropolitan was promoting growth around its stations, but appealing mainly to what we would now see as the ‘middle classes’ of managers, rather than the large group of clerks who couldn’t afford the fares - the London and Birmingham Railway had done the same in the 1840s along what is now the West Coast Main Line. In any case the financial and organisational structure needed to build and sell the thousands of houses was not yet in place: that was to come in 1919, with the setting up of the Metropolitan Railway Country Estates Company to buy the land required for the huge developments envisaged to ‘provide superior houses in the rural countryside near London, but also to create new passenger traffic’. The first purchase was at Wembley Park: the Cedars estate at Rickmansworth, initially quite small at only about 45 acres, followed shortly afterwards, and the expansion continued during the 1920s, reaching out to and past Amersham. Nor was it all the work of the Metropolitan Railway itself: Moor Park mansion and estate was bought by Lord Leverhulme after the First World War expressly for housing and a golf course, and was advertised as ‘the gateway to the Chilterns’: ‘quietude and seclusion (without isolation)’ were promised, with houses costing ‘from £1000’ – definitely in the upper range – in private roads, as they still are today.

There was some freight traffic, and it affected Rickmansworth when much of the sand and gravel dug out of what is now Sabey’s Pool and the Aquadrome was taken by boat (including special gravel punts built by Walkers) to a wharf just next to the Met line where it crosses the canal close to Lot Mead below what is now Long Valley Wood. The gravel went from there by train, mainly to west London, Wembley and Harrow.

So Metroland, a term first used in 1915, was well established by the mid-1920s, and continued apace for a few years more. The Watford branch, including Croxley Green, was opened on 31 October 1925, the same year that electric trains began to run to Rickmansworth (steam was used from there for the long climb up to Chorleywood and the Chilterns), and trains went direct to London with an additional shuttle service between Watford and Rickmansworth. But the branch could not be completed to its pre-war plan: the embankment required to take the line to the town centre attracted great opposition, and the line terminated over a mile from the town, although the station made sure that west Watford became firmly Metro-land and after a couple of years provided a shuttle bus service to the town centre via Vicarage Road and Watford High Street.

All through that Metroland, including Cassiobury Park, Croxley Green and Rickmansworth, rows and roads of semi-detached and detached houses and bungalows appeared, with a first venture into lower-cost housing starting in 1929. The Cedars Estate in Rickmansworth had by the 1930s grown to cover over 600 acres of ‘residential country estate… adjoining the old-world country town of Rickmansworth…’, and was offering (through the local sales office in Meadow Way) luxury detached houses for £2,150. The absorption of the Metropolitan Railway into London Transport in 1933 came at the peak of Metroland development, but did not stop it, and London Underground continued advertising houses in (for example) Rickmansworth from very early in its life. One hint at the effect on Rickmansworth comes from the opening of the Odeon cinema in 1936: one had been opened in 1936 at Rayners Lane, reflecting the new leisure habits of the new inhabitants, and one wonders whether Odeons were following the Metroland developments to towns opened up in this way.

[1] Reproduced in The Rickmansworth Historian, issue 1 (May 1961), pp.13,14.

By the start of World War 2 it was clear that the new world created

in the Chiltern hills and their approaches had destroyed great swathes

of the countryside that it had offered to so many Londoners, and

post-war attention to the Green Belt stopped such rapid expansion: but

the die had been cast, and the effect on what had become ‘Metro-land’ was

fixed for ever. A wonderful model of Rickmansworth Station completed (after several years) in about 1962 show the station and its environs was filmed by our intrepid reporter in 2023, and you can see it here.

Steam was discontinued on 9 September 1961, but the nature of Rickmansworth and Chorleywood (and Watford and Croxley Green) as London commuter towns continued to this day - people in large numbers didn't work here, but they lived here. This is Metro-land.

and Chorleywood.