A Rickmansworth Farmer - the diaries of John White of Rickmansworth

A co-creation project with the University of Hertfordshire

If you’d like to be involved in this really important local history project please contact us.

This might be of interest to local schools and groups, as well, and local businesses might want to take part.

And we’re now ready to give talks about this Rickmansworth farmer – use the same contact to find out more.

The story of the diaries

The museum received a very significant donation in August 2022.

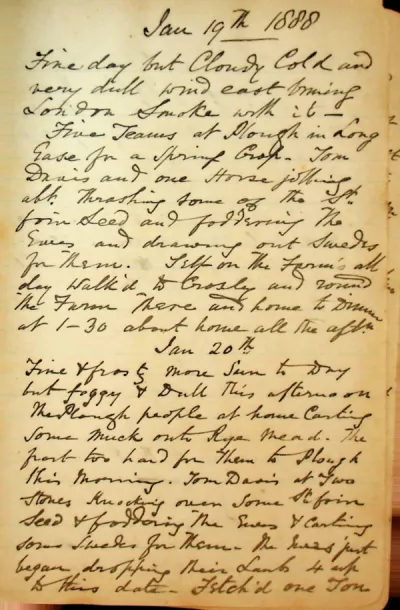

John White (1813-1904) farmed Parsonage Farm in Rickmansworth from before 1840 to the end of his life at the age of 90. He was believed to have kept a personal diary every day, recording not only his agricultural activities but also his personal life and doings. Extracts by Kenneth Jones, a well-known Watford local historian, appeared in three issues of The Rickmansworth Historian in 1970, which hinted at a great wealth of material in the diaries, but until recently we had no idea where the diaries were. An article in Historian 50 (2004, but written much earlier) told us that they were in the care of Canon John Paget, once of Watford but then retired in Chichester: but that was over thirty years ago, and we still had no way to contact the family. An appeal this year in the Watford Observer got no response.

But we had, tantalisingly, the family bible, which the chairman of Rickmansworth Historical Society had been offered by a lady in another part of the country who found it in an Oxfam shop: it’s now on ‘permanent loan’ to the museum. The rewards for finding the diaries, and being allowed to see and even copy them, would be clearly be very great indeed: but how to find them?

Helped by the census and other on-line records, we knew the family story quite well. John and Sophia White had just one child, their daughter Fanny, who in 1864 had married one of John’s farm students, William Hounsfield. So we had a family name. But the Hounsfields had ten children, so we had rather a lot of family names and over 120 years in which they moved around, so the trail was a bit tangled – and of course had no contact details, and no certainty that they had the diaries. But we noticed that a family name of William Hounsfield had been adopted in naming his children, which narrowed the search quite a lot, although still with no contact details.

They came from Companies House – a gentleman of that name had been listed, albeit 30 years ago. With nothing to be lost by trying a punt we wrote to that address, although without much hope of a result.

But a week later, we got a wonderful e-mail - confirmation that I had the right man, and that he thought he could help. And what help he gave - within a month! Remember that these diaries are family heirlooms kept carefully by the extended family for over a hundred years, so I was really delighted when he said that the family had decided that the whole of the collection they had (there are gaps) should be donated to Three Rivers Museum. When could I come and pick them up?

This is an act of extreme generosity by the family, and way beyond my wildest dreams. I was both delighted and overwhelmed, and so it was with some trepidation that we collected them from the family on 9th August 2022. It was a very pleasant meeting, and the result is that the diaries, repacked into archive-standard boxes, are now safely in our store, a few hundred yards from Mr White’s Parsonage Farm house.

What have we found so far?

What we have is, as we hoped, quite remarkable – and there’s much more than we realised. John White himself wrote a deeply personal account between 1841 and 1896: some of the volumes were passed around the family in the 1930s and probably went to Canada and Australia, so they probably won’t return, and there are gaps, notably in the early years. But we have most (22 of the 33 volumes), and they provide a wonderful insight into how life was round here – what he did, who he worked and did business with, who he employed (and where they lived – often in the farm house, later than has been believed for Hertfordshire), what else was going on… all quite aside from his detailed accounts of the work of the farm.

But there is far more: William Hounsfield’s farm diaries from 1865 to 1896 are also here, although more factual and prosaic. And so are much of the farm financial records for both farms - it is, apparently, unusual to have such detailed accounts from this period, and we think they alone are a remarkable find and with many fewer gaps. Mr White was a churchwarden for fifty years, and his observations relate to that activity as well. There are also a number of other documents: John White’s will (after probate), a copy of a hand bill for a ploughing match in 1859, the 1806 21-year lease to John’s grandfather of the farm in which William Hounsfield was later installed on his marriage – and the marriage settlement under which that was done in 1865; and a host of documents relating to the probate of his estate on his early death in 1896.

We have a grave duty to keep them safe, and treat them correctly. So the first thing has been to list, catalogue and accession them in full. Then, we’ve digitised the diary volumes, so that they can be worked on without handling the originals – that has been pretty well completed. A team of fourteen volunteers has taken on the transcription – not an easy task, but already fourteen of the twenty-two volumes we have are done, and all the others are well in hand. We have also just had back most of the other papers after professional digitisation by TownsWeb Archiving, under a grant from them for which we’re most grateful, and they’ll form the nucleus of Project Harvest.

What's Project Harvest?

The full name is “Hertfordshire Agriculture: Research into Victorian Enterprise for a Sustainable Tomorrow” (HARVEST).

Starting in April 2024 and running to October, it's exploring this amazing collection of truly historic papers to discover lessons on sustainability for the 21st century. A research project involving students and staff from the University working with our museum volunteers, it’s part of the Heritage Co-Production scheme funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) with a grant administered by the University. It will provide some of their business students with a challenging case study to find out why John White was successful 150 years ago when so many of his friends and colleagues were struggling. And crucially, what can we learn for now?

Project HARVEST is led by Dr Sue Davies and Dr Derek Ong, and it’s very exciting new ground for the Museum - we’re very pleased to be part of it. It will have a number of outcomes, including at least one paper, an exhibition in the museum and to travel elsewhere, and a couple of ‘workshops’ to allow exploration of what we’ve discovered.

What happens after that?

Eventually we’ll want to publish the diaries, with a context and commentary, perhaps in a book (rather large – we already have approaching 1000 pages of transcription), or on line – there could well be several books to be written. All that is a huge amount of work, and will require a considerable team at work for some time, probably years. So we have quite a project.

The timespan is especially significant, becuse the terrible weather (winter, spring and summer) from 1874 to 1895 led to a severe agricultural depression acrtoss the country, not least in Eastern England. What John White has left us will tell us a great deal about that period and how he dealt with it: it gives real local examples of what's already in the agricultural histories of the time.

But that’s not all. We’ve hardly started to read the diaries properly, but already we know how John White felt about others affected by what was happening here - for example, after a damaging storm Mr White was concerned about the seafarers out in it. The year 1879 was especially bad: the weather had been disastrous for farmers (in October he wrote that he’d started haymaking on 30 June and finally got the corn harvest in on 9 October) – he thought he would survive, but he knew that some of his colleagues would not. At the New Year he was horrified by the Tay Bridge disaster in Scotland, in which a railway bridge collapsed killing all 75 people on a train; and in his year-end round up he noted “one of the most eventful years on record and most disastrous to the agriculturalists of this country and fraught with many melancholy events from beginning to end. Two most disastrous Wars, the Zulu & the Afghanistan, where so many valuable lives have been sacrificed”. So we know at first hand how some people in Rickmansworth tended to feel about both national and international events – and this runs through the whole 50 year set.

But his main interest was much closer to home. The wedding of their daughter Fanny, the arrivals of their eleven grandchildren, the death of one of them at the age of two, the sudden death of their son-in-law - all are recorded in a way which tells us a great deal about how Victorian people saw and felt about these things. The wedding of the first grandchild, and the arrivals of the first great-grandchildren, are mixed in with the harrowing account of the last weeks of the life of Sophie, his wife of 55 years who had done so much for the ‘lads’ of the town, before his own heath declined so that he had to suspend his diary in 1896 – he lived to 1904.

And we also find his very personal feelings about some of his own long-serving staff – Jack Halsey was his much-loved shepherd for more than forty years, and he notes with concern and without blame the absence through sickness of his workers. He gives us an idea of the work done by women and men both as casual and as hired labourers, and how the various ‘farm pupils’ got on (not all proved suited to the profession). But most of all, we’ll be able to track his progress through economic depression, and see what it meant to him and his Rickmansworth and indeed Hertfordshire neighbours.

Can I get involved?

Probably. The work will take years to complete, and there will be enough to occupy a whole team of people: but it’s moving.

If you’d like to be involved in a really important local history project please contact us.

This might be of interest to local schools and groups, as well.

And we’re now ready to give talks about this Rickmansworth farmer – use the same contact to find out more.